Selingan island, part of Turtle Island Park, is the only island in this region that tourists can visit. The tracks of a turtle are unmistakable. As the sea turtle crawls, it pushes back sand with each flipper stroke, creating a 25-inch wide double trail of sculpted sand. The sweeping limbs of the sea turtle, undulating from ocean to the dune and back, mark a distinctive path of a labor-intensive journey. She digs her nest and releases (in our case) 93 ping-pong ball-size eggs. These private, awkward moments are the moments in which scientists know sea turtles best. We watch her big ancient eyes, her bulky, ungrateful form, and we recognize the impossible hope that follows her flippered path.

The eggs are harvested immediately by the naturalist for placement in the hatchery where they are outside the reach of predators or poachers. Each nest within a fenced enclosure is marked with the date, and number of eggs placed, which will later be compared to the number of hatchlings that emerge.

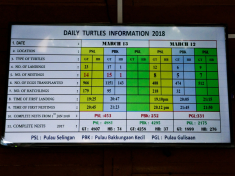

The hatchlings that emerged from their nest today (from 60 days prior to our visit) were released on the beach where infant turtles rush to the waves. We feel the impossible hope of these tiny creatures pushing their bodies into the vast, deep ocean to the tangles of sea grass or the sharp teeth of propellers and predators. We understand it. We’re afraid for them, but we have hope too, that some will make it, some will come back just like their mothers did, chasing the same moonlight their grandfathers’ grandfathers chased, too, for millions of years before them, before we humans ever set foot on any shore to watch. Over the entire night the conservationists helped 14 turtles nest; with a total of 966 eggs transplanted and 179 hatchlings released to the sea.